The most important political unit to centaurs is the clan, which has resulted in a more fragmented political climate than found among other sophonts. Because the size of a clan is limited by the amount of offspring a single matriarch can produce and the number of adult individuals that unit can support and control, associations larger than about 50 are almost always interclan alliances, and the bonds of those alliances are always subordinate to bonds within the clan. As such, there is essentially no way for nations or empires to form. Although territorial wars between settled clans are common, clans that absorb more people or territory than the family can manage will almost always fracture into new family groups.

However, within the past 500 years, there has been a rising population of urban settled clans. Usually clustered around fertile ground for grazer and invertebrate farming, or around shorelines and rivers plentiful with aquatic animals, the borders of clan territories shrink and touch each other while commons areas grow alongside more complex rules about interclan politics. These cities function more like collections of micronations than cohesive political bodies, but it has become more and more common for clans to collaborate on large scale projects like railroads and industrial production. Ownership and usage rights of large projects like this is often determined by which clans contributed and how much, recorded on grooved tablets in clan libraries. Infighting is common and ownership transference upon the fracturing of a large clan is frequently messy.

Clan structure at its most basic consists of three tiers: a fertile female (the matriarch), their mates (the entourage), and the matriarch’s children (workers). The worker group often includes post-fertility matriarchs, and some unrelated centaurs in large clans.

Generally, the matriarch is the dominant female of the clan and gains that status from social climbing and dominance struggles with other females in the group. Female siblings from similar age brackets tend to be in direct competition with each other and can become overtly hostile when the current matriarch’s health or fertility wanes. Some clans settle the matter through ritualized combat between prospective matriarchs, but most commonly, the next matriarch is chosen by the current one from their children. Sometimes, much more rarely, they will choose a favored unrelated female from their entourage or worker pool. Matriarch election by majority is also sometimes observed in small clans.

Some centaurs, such as those in the Auolut and Bii regions, have a caste system attached to the clan structure that has a social tier above the current matriarch that includes clan elders, particularly ex-matriarchs; and divides the worker group into a higher tier that includes children of the matriarchs and a lower tier of unrelated, married-in workers. In these systems, new matriarchs are more likely to be chosen by the highest caste than the current matriarch.

Marriage to a clan can refer to two different things.

Worker marriage is when a worker from a different clan is married into a new clan’s worker pool. This is far more common among settled clans, especially larger ones, and is usually done as a way of acquiring members with new skills, strengthening ally bonds, or bulking up member numbers. Although unrelated workers often form romantic and sexual bonds with each other, it tends to not be a primary reason for marrying in new workers. Sometimes worker marriage is carried out by force after bloody interclan conflicts and territory invasion.

Entourage marriage is when a centaur is married into a clan matriarch’s entourage pool. This is done for the purpose of siring larvae with the matriarch, increasing the number of centaurs caring for the clan's infants and young children, and forming strong alliances with allied clans.

Clan formation is driven by female competition for reproductive exclusivity, and one of the underlying forces of that is pregnancy aggression.

Pregnant and nursing female centaurs experience higher levels of aggression, particularly towards other females with children or towards unrelated children. This is an abstract feeling that has been reinforced through social reproductive evolution, comparable to mate guarding and male-male competition behaviors in humans. While those behaviors in humans have lead their societies to most frequently organize into monogamous or polygynous structures, these feelings are not universally experienced or socially managed in the same ways. Pregnancy aggression in centaurs is a similarly tangled ball of individual, cultural, and systemic differences.

Generally, centaurs organize themselves in ways that minimize the amount of competition-related conflict their social groups experience. Getting pregnant without matriarchal permission is avoided, and that is sometimes culturally enforced through rules about recreational sex between workers. Unplanned pregnancies and infants are generally terminated as early as possible, often by the pregnant party. Clans split when they become too large to maintain matriarch exclusivity, often at the impetus of the original matriarch. Some clans with less pregnancy-aggressive cultures and attitudes will organize clans to accommodate multiple matriarchs (e.g. the coastal Shess), or adopt more fluid clan territories (e.g. the Biing islanders).

Most clans have a dominance hierarchy with a single female at the top, but this is not always the case.

Some clans on the southern coast of the urban Shess peninsula and Pahk region have two or three matriarchs with a shared pool of workers, and sometimes shared entourage pools. These clans tend to be enormous and control large territories, but can be unstable—shattering a multi-matriarch clan can get very bloody.

Non-hierarchical clans are rare. They are most commonly found among the Biing islanders, who live in cooperative settlements of multiple small clan groups with shared territories. While typically a household will only have a single breeding female at a time, division between worker females and matriarchs is low. Females of a Biing house may take turns having litters, share mates and entourage pools, and help their sisters and neighbors rear young. In some ways their family groups are closer to those of bug ferrets or polygamous humans.

Anarchist movements are growing in popularity among young urban centaurs who were born post-contact, many of whom feel simultaneously stifled by traditional clan structure and manipulated by alien agendas. Anarchist centaurs often attempt to form non-hierarchical groups or become self-sufficient individuals, to mixed success. They often model their groups after the family systems of the Biing islands, but these attempts tend to fall into instability, and are viewed as disorganized and childish attempts to thwart natural order by more powerful traditional clans. Non-hierarchical clans in rural areas are often seen as easy-pickings by bandits and hostile local clans.

Clanless centaurs are vagrants with no territory (or, very remote territories) nor a unified group they belong to. They sometimes drift in and out of bandit groups and bachelor clans, and are usually met with a sense of mistrust or pity. Those who stay intentionally clanless are considered to be mad hermits, those who can’t seem to stay in a clan without being ousted are considered unstable liabilities. Many clanless centaurs are mentally ill, and they are more common in urban areas mostly because being clanless in rural areas or on nomad paths is often a death sentence; either by hostile centaurs, wildlife, or the elements.

Most centaur concepts of gender are strictly linked to sex, as sex is a vital part of clan organization. Despite this, its importance in the social lives of centaurs is often subordinate to clan roles and dominance struggles within those. Atypical clan structures and third genders also exist and have their own unique sets of struggles.

In some cultures, such as the Shta, Chuchae, and Daewirgh, the entire worker class of a clan is considered a kind of neuter gender unless they are transferred to a position in the active reproductive hierarchy. Homosexual activity among workers is also often accepted by centaurs, while heterosexual activity is much more heavily policed because of its potential for worker pregnancy. Cultures that view the worker class as neuter tend to have a more relaxed attitude to sexual relationships among workers of any sex. Nomadic groups tend to have the strictest attitudes about sex among workers, and a higher degree of cultural gender dimorphism than settled clans.

While centaurs are very androgynous, an exception to this is the prominent spinnerets of female centaurs. In some cultures, the spinnerets of worker females are amputated to eliminate them from being able to raise larvae of their own. This may be done preemptively by a domineering matriarch, or it may be done as a punishment for unapproved pregnancy. Some centaurs, however, voluntarily amputate their spinnerets and may crossdress and adopt traditionally male pursuits, such as propositioning for entourage positions and joining bachelor clans. The Shess word for this kind of third gender is “eshik,” literally meaning “cut.” Social acceptability for eshik varies but among the Shess, it’s not uncommon for entourages to contain a few of them. While they cannot sire offspring with a matriarch, marriage with an eshik can still serve all the same socio-political functions as marriage with a male.

Centaur males are overall far less likely to adopt female roles and mannerisms, and less likely to be taken seriously when they do so. Since there is only one dominant female in most clans, and the ability to produce larva is considered vital to the position, the female roles that they can adopt are limited and considered more neuter-sex than anything else. Despite this, exceptions still exist. Terms to refer to them typically translate to “crossdresser” or “false female” but the preferred self-identification term in Shess languages is “mujash iank” or “born barren,” comparing themselves to post-fertility (barren) matriarchs. An infamous mujash iank is Taewach, who was the legendary bandit leader of an all-female clan. They were discovered to be male post-mortem by a group of settled clans the bandits had unsuccessfully invaded.

Bachelor clans are the most common and socially acceptable type of atypical clan. These are especially common in nomad groups, where mature male children of the matriarch may be ousted if the clan grows too large. These bands of ousted male centaurs rarely have any territory and will travel together among settled clans or between different nomadic bands, paying for their guest stays in entertainment, sex work, or specialty goods and services. Often the members are seeking marriage and use their guest work as a way to advertise their value to the clans they stay with. Most bachelor clans, although they contain tight friendships and romantic bonds, are ultimately doomed to evaporate as the members settle down and marry into clans they visit. Some settled clans are hostile to bachelor clans, as they have a reputation for being thieves and seducers.

Female clans are rarer and have a far worse reputation than bachelor clans. These groups often form as a result of internal strife within a large clan, where several worker females who were struggling for the matriarchal position are ousted, or leave after getting fed up with other social conditions. While good faith clan schisms usually include mixed sex groups that already contain a designated matriarch, all-female clans often have tumultuous hierarchies. Just like bachelor clans, these groups often have tight romantic bonds within them and can find stability in those—but in many cases, this is disrupted by pregnancy or the addition of male members. Bachelor clans usually end by bleeding too many members; female clans usually end by shattering from internal power struggles or transforming into a typical clan structure with one matriarch. Some all-female clans hold territory, but many are nomadic or travel between settled clans paying for guest stays with labor. Quite a few are bandit groups who make their living in less scrupulous ways, though, and most centaurs approach roving groups of females with suspicion. Sailor (and pirate) clans of all females are also fairly common, and strangely seem to have more stable hierarchies than land-based female clans.

Bachelor clans are often far more tolerant of gender-variant individuals and it’s common for them to include crossdressing females and eshik. Mujash iank in female clans are more likely to be lying about their identity to fellow clan members, or treated with emotional distance and suspicion.

Pre-contact centaurs are frequently described as being in their “Radio Age,” which for humans brings to mind their WWI era, but the reality is not so symmetrical. Almost half of pre-contact centaurs were nomads living hunter-gatherer or herd-driving lifestyles with very little access to electrical technology. Meanwhile, technological development in settled centaurs varied due to the fragmentary nature of clan politics.

While multi-clan cities might have contained enough industry to support internal infrastructure like plumbing, factory sites, and electrical grids; large projects that extended into surrounding territory were often doomed. Railways, for instance, require the agreement of all the rural clans whose territory the rails are built through, and social upheaval within each of those clans may result on contract renegotiation, armed conflict, or project delays. And on the other end, clans with workers who specialize in rail-laying trades are often not willing to work very far from their home territory for a project that only fractionally benefits their own clan.

As a result, centaur homeplanet transportation infrastructure outside of the well-trodden nomadic circle is abysmal. While centaur technology within larger cities (particularly on the Shess peninsula) could be quite complex, including electronic radios, fridges, heaters, audio recorders, cameras, portable batteries, motors, and more; these artifacts were often bespoke items made by craftspeople within the city and not widely distributed. The most complex metal possessions of rural settled clans within a 2 day walk of cities might only be hunting rifles, as a happenstance of their roads being too inconvenient to connect to an electrical grid and their terrain too rough to drag something heavy, metal, or wheeled down. Water routes were by far the best traveled for distribution of goods between settled clans, but large sailing vessels were rare. Vessels large enough to make significant ocean voyages are usually the home and income source of an entire large clan.

First contact introduced chaotic change to centaurs’ technological landscape. Flying transportation shortcut their ground infrastructure problems by flying over the clan territory rails would have to be built through. Extremely slow creation and dissemination of technology was shortcut by BFGC subsidized access to cheap, factory produced, incredibly powerful (and often more portable) electronic devices. Ironically, it was nomads who were quickest to mass-adopt and spread alien technology, finding a great deal of use in solar-electric ground vehicles and cell phones in their massive caravans. Settled populations are more divided, with most cities having anti-adoption clans who want to resist alien technology as it destructively replaces centuries of unique centaur artisan work, and pro-adoption clans who see alien technology as a way to dramatically improve centaur quality of life and quickly gain respectability in the galactic community.

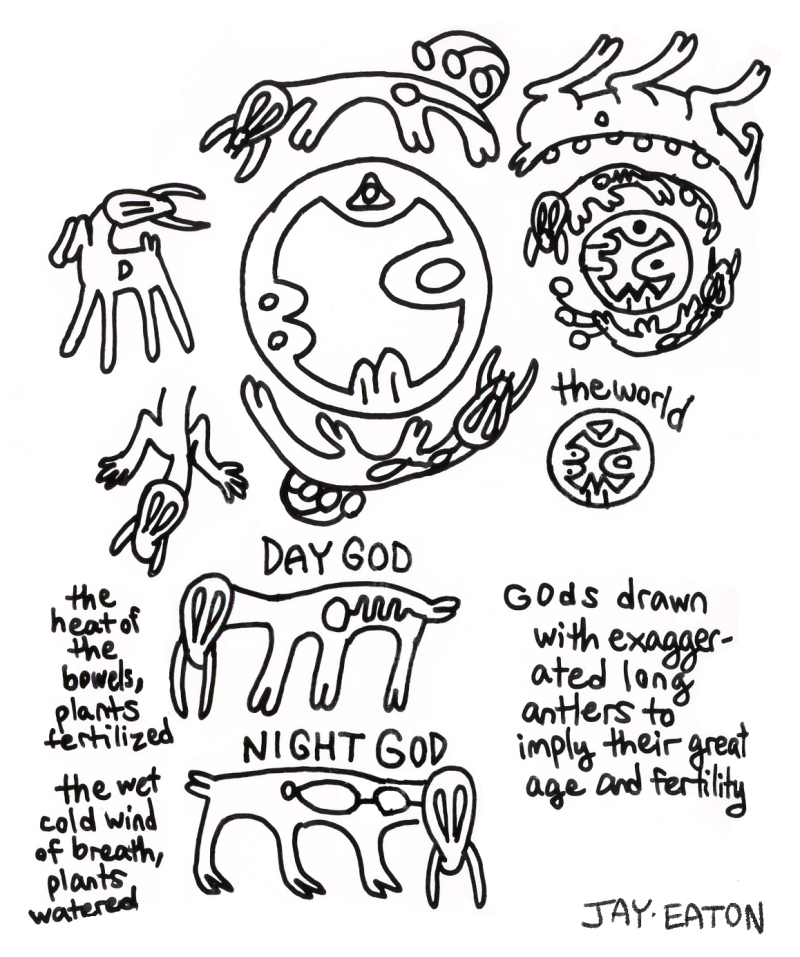

Settled clans tend to have a patron spirit tied to the land they live in, or the main means of sustenance or commerce in the area. This patron spirit may also represent the matriarch of the clan, or there may be an additional spirit for that purpose. This spirit is believed to pass from the body of the matriarch to an eligible heir when the matriarch reaches the end of her fertility and stops growing antlers. Depending on local custom, this spirit may be purposefully guided into the next chosen matriarch, or sometimes the spirit is believed to choose for itself, and spiritual divination is performed to determine the heir. Depending on region, nearby clans will often share a handful of other gods associated with creation, the natural world, divinity, or social forces; but these are rarely the subject of more devoted spiritual practice or attention than the spirit of the clan and matriarchal rights.

Settled clans tend to have a patron spirit tied to the land they live in, or the main means of sustenance or commerce in the area. This patron spirit may also represent the matriarch of the clan, or there may be an additional spirit for that purpose. This spirit is believed to pass from the body of the matriarch to an eligible heir when the matriarch reaches the end of her fertility and stops growing antlers. Depending on local custom, this spirit may be purposefully guided into the next chosen matriarch, or sometimes the spirit is believed to choose for itself, and spiritual divination is performed to determine the heir. Depending on region, nearby clans will often share a handful of other gods associated with creation, the natural world, divinity, or social forces; but these are rarely the subject of more devoted spiritual practice or attention than the spirit of the clan and matriarchal rights.

Sunchaser and nightchaser nomads, despite often being on opposite sides of the globe, have a more cohesive belief system than the settled clans. Many landmarks along their continuous path are considered sacred rest sites, and messages in nomad script and beads are often left for their distant kin.

The nomads' shared creation belief is that the world was born by the matriarch of the sky, sired by her entourage of three moons, whose numerous other children cover her back as stars. Two of her first litter spun themselves into a single cocoon as larvae. It was too large and round, and fell off the sky mother's back, becoming their planet. The two larvae ripped out of opposite sides of the cocoon, forming the great ring continent with its jagged tear of high mountains down the middle. The fluid of their shed larval skin became the two oceans on either side.

The two sisters saw they had fallen from their mother's reach, and each declared themselves as the matriarch of their new territory. One sister, who was the day, wanted burning sunlight to forever fall on the planet. The other, who was the night, wanted eternal dark and ice. Each sister demanded the other recognize her authority and leave. The sisters began to chase each other in order to drive the other off their territory, but because the land is one great ring, they ended up running in an eternal loop. The chase exhausts them, and every solstice the sisters rest at opposite poles, scorching and freezing them before they regain their strength to chase the other. And although their pause to rest makes the poles unlivable during the solstices, they ultimately leave the land more fertile in their wake. The nomads enjoy the great seasonal bounty of the poles in the fall and spring, when they pass through. Sunchasers follow behind the day god, who bore their ancestors from her back, entering the poles at autumn. Nightchasers follow after the night god, who bore their ancestors, entering the poles in spring.

The two sisters saw they had fallen from their mother's reach, and each declared themselves as the matriarch of their new territory. One sister, who was the day, wanted burning sunlight to forever fall on the planet. The other, who was the night, wanted eternal dark and ice. Each sister demanded the other recognize her authority and leave. The sisters began to chase each other in order to drive the other off their territory, but because the land is one great ring, they ended up running in an eternal loop. The chase exhausts them, and every solstice the sisters rest at opposite poles, scorching and freezing them before they regain their strength to chase the other. And although their pause to rest makes the poles unlivable during the solstices, they ultimately leave the land more fertile in their wake. The nomads enjoy the great seasonal bounty of the poles in the fall and spring, when they pass through. Sunchasers follow behind the day god, who bore their ancestors from her back, entering the poles at autumn. Nightchasers follow after the night god, who bore their ancestors, entering the poles in spring.

Although nomadic clans often have spiritual inheritance between matriarchs, similar to many settled clans, they will often refer to themselves as belonging to the clan of one of the two sisters, or refer to the day and night gods as the undying ancestral matriarchs of all centaurs. Despite having the typical conflicts between clans for resources and power struggles for matriarchal authority, nomads have a larger shared cultural identity than most settled clans do with one another.

A relatively recent development among settled clans is large cities composed of multiple clans. These regions tend to have much more cohesive spiritual backgrounds, and often hold a local deity personifying a landmark or trade in high regard, and the clans of the city give tribute to that deity, agreeing to cooperate with one another to share the bounty of the region and better their neighbors. These cities, many of which are along the travel routes of nomadic bands, frequently borrow spiritual ideas from the nomads about the creation of the world. Depending on their culture they may classify local deities as being either the children of the night or day sister, consider one sister to be an evil spirit, or conceptualize the day and night as being a single dualistic entity. The Shess region favors the latter interpretation.

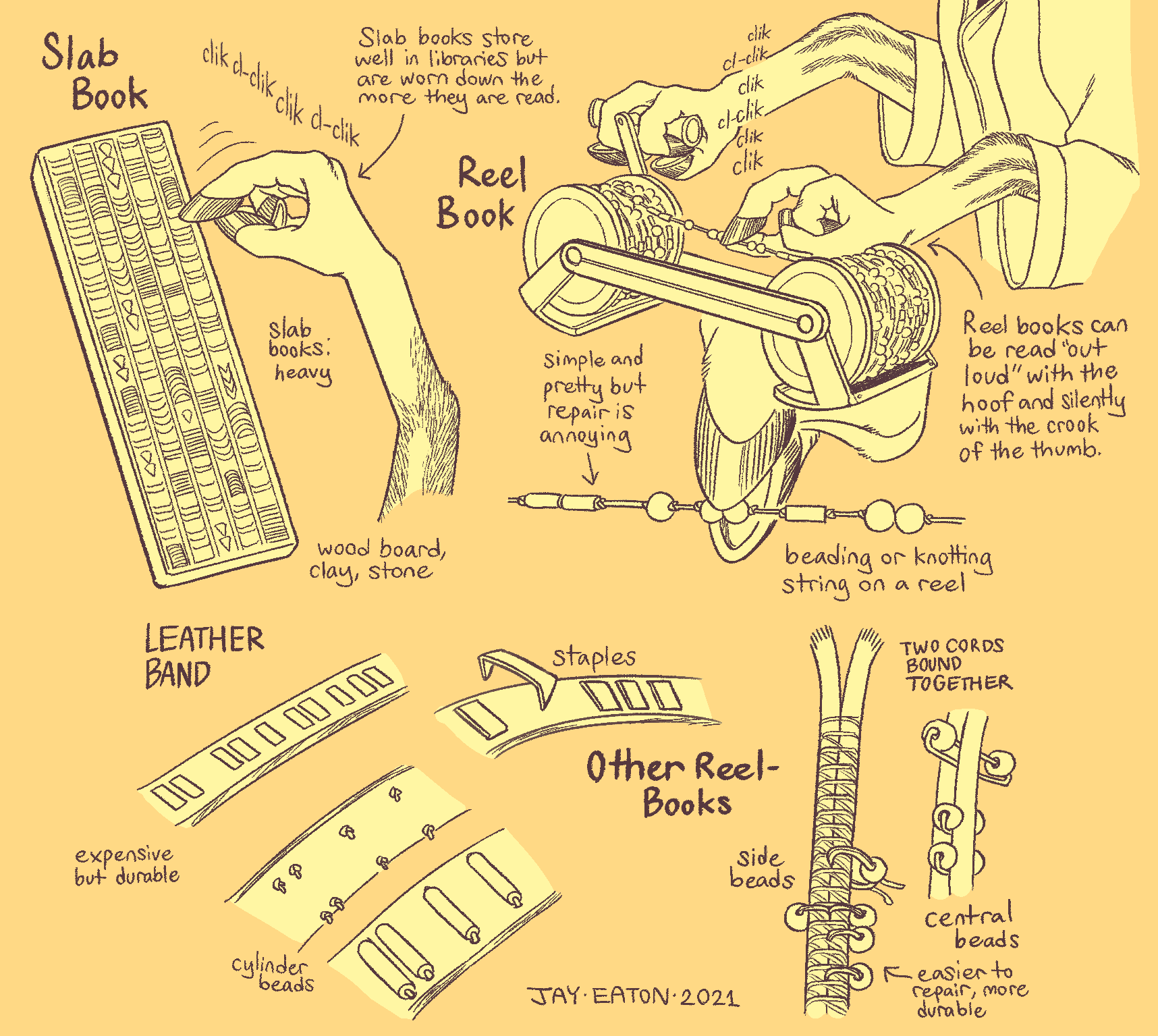

Centaurs have impressive long range vision, but compared to the other sophonts their short range vision is poor and blurry. Dense information storage can be a challenge– in addition to rich oral history traditions, tactile languages of various kinds are found all over the centaur homeplanet. Settled centaurs tend to prefer slab books, which are heavy but store well; and nomadic centaurs tend to prefer reel books, which are less durable but are light enough to be worn as jewelry. Slab books are made of clay and pressed with a wooden style to create a series of bumps and ridges that can be read by dragging a hoof over it after the clay has been fired. Reel books are a string with a series of beads and knots of different shapes and frequencies, which are read by pinching the strand between two fingers and drawing the string through, either by hand or with a reel device. Both slabs and reel books can be read “aloud” by allowing the hoof to hit the ridges audibly. The effect is comparable to Morse Code.

The nomadic clans have the most comprehensive written language on the homeplanet, but it tends to used exclusively for signage and written with large pictographic characters that can be read easily at long and short range. It also features an unusual non-linear written sentence structure, with subjects, objects, and adjectives/adverbs being placed around the verb; and conjunctions trailing off the subject to attach new clauses. As such, sentences can often be read in different orders depending on the presumptions of the reader. Some theorize that this non-linear method arose to help comprehension with poor visibility or limited vocabulary, since position can help the reader guess the meaning of symbols.

Since the introduction of alien technology, reading glasses and contact lenses have become increasingly common on the homeplanet. Previously, wearable magnifying lenses had existed, but were expensive and primarily used by specialized craftspeople. Alien writing systems have been adopted by many centaurs for transliterating their own spoken languages, since they are more convenient for communicating on alien screen devices, threatening native oral traditions and tactile writing systems.

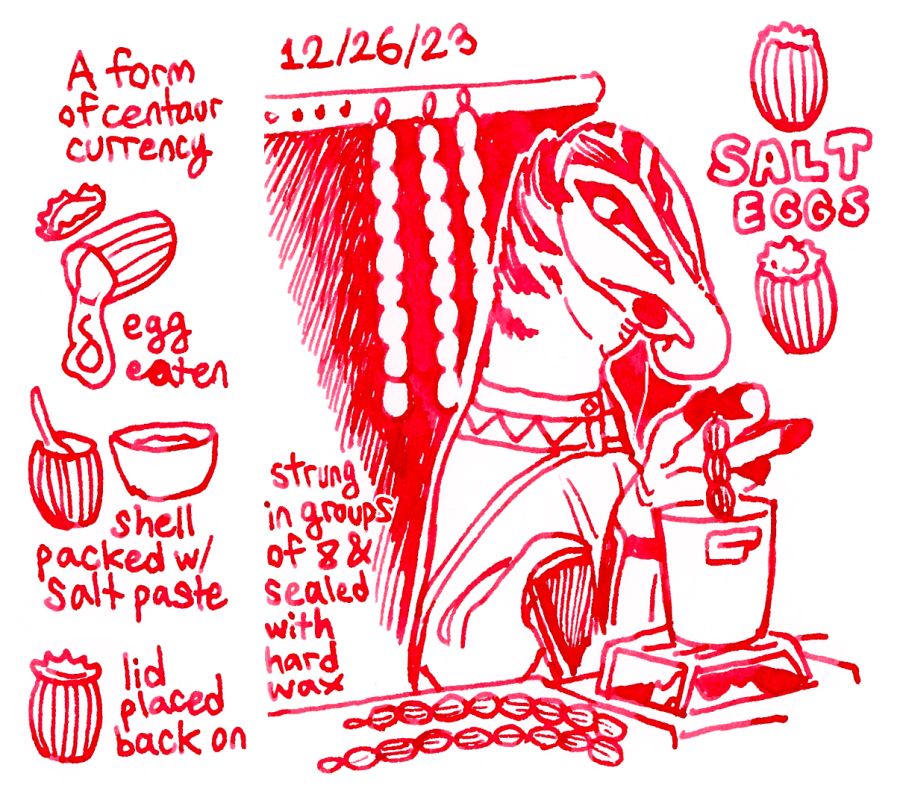

Because of the fragmented nature of centaur politics, barter systems are more common for trade between different clan groups. While metal items, trinkets, beads, spices, drugs, and salt are often used as small portable items of value; their regional value varies and coin-like standardized currency is rare. Many settled clans also barter in services, allowing other clans and nomads to stay in their territory and eat with them in exchange for various kinds of labor.

The Shess peninsula uses a kind of currency made from empty livestock invertebrate egg cases packed with a mixture of salt and mashed starches. These are threaded length-wise on a cord and allowed to dry completely, then dipped in wax to seal. These corded eggs are commonly used for a placeholder of value that can be conveniently portioned into chains or chain segments. These originated as a trade goods from nomads collecting salt from flat deposits on the south pole, and salt egg currency is occasionally seen in Shta and Pahk regions as well.

The urban Pahk also use cast gold beads in different sizes and textures as a currency, which are more commonly seen in use in the east hemisphere among the Bii, Auolut, and Chuchae.

Nomadic clans typically produce only leather and woven animal fiber materials, and complex woven fabrics made from plant fibers are manufactured by settled clans (along with a wide variety of other materials, including beads and metals). Trade between the two is common and nomads are often seen wearing an eclectic variety of trade goods with or on their native garments.

A classic nomad garment is a heavily pocketed leather pant that covers the lower four limbs, with a bare chest in fair weather.

In hot weather, nomads may wear little more than loincloths and pockets. In cold weather, furs and felted animal fiber overjackets are commonly worn, and sometimes gutskin jackets and hats in the rain.

Sunchasers will hold festivals around their equatorial rest sites, which frequently involve shaving patterns into the short feathers of the body, dying and body painting, and tying flashy banners to the body to shake and flick while dancing. Outside festivals self-decoration with beaded or knotted necklaces and bangles is common, and religious scripture is commonly worn in the form of reelbook strands.

Nightchaser cultures will often pierce the upper part of teenagers’ trunks with a bar piercing when they come of age. Adults may acquire more of these in their lifetime, as well as incurrent and excurrent nostril piercings, for different life events and changes on hierarchical position. Older nightchasers have the most piercings and they are sometimes used as a visual shorthand for authority.

The classic cultural garb of the lower Shess peninsula includes a short cape or chausses worn on the upper limb pair, A loose jacket or pants on the midlimbs, and a shirt or trousers on the rear limb pair.

The area is known for its plant fiber cloth, reed weaving, and glass beads, and clothing is frequently decorated with these elements. Geometric patterns influenced by reed weaving are a common motif, as well as long curved “fish rib” beads on knotted cords that wobble and swing as the wearer moves.

The area is known for its plant fiber cloth, reed weaving, and glass beads, and clothing is frequently decorated with these elements. Geometric patterns influenced by reed weaving are a common motif, as well as long curved “fish rib” beads on knotted cords that wobble and swing as the wearer moves.

Shess footwear includes a variety of boots, sandals, and hoof clips. Urban centaurs rarely go unshod because the paved streets are rough and grind down the hoof claw too quickly. Trimming the hooves down manually and protecting them with shoes is preferred.

Shess practice decorative antler staining, carving, and scrimshaw, usually with geometric patterns. These decorated antlers are sometimes saved after they’re shed and used for art projects, tool handles, or clans’ ancestral keepsake walls.

Shess worker males and females wear similar garb, although females are often assigned more labor intensive jobs that require more durable and less showy clothing. Entourage members tend to dress in ostentatious flowing fabrics with tall beaded hats, with more lavish clothing showing off the wealth of their clan. Makeup powders that redden the trunk lips and increase the contrast and symmetricality of their facial markings are common. Matriarchs show off by wearing fine woven fabrics, but usually dress with less eye-catching colors and swinging beads. Short boarded hats with woven bands are common as a matriarchal status marker.

Shess worker males and females wear similar garb, although females are often assigned more labor intensive jobs that require more durable and less showy clothing. Entourage members tend to dress in ostentatious flowing fabrics with tall beaded hats, with more lavish clothing showing off the wealth of their clan. Makeup powders that redden the trunk lips and increase the contrast and symmetricality of their facial markings are common. Matriarchs show off by wearing fine woven fabrics, but usually dress with less eye-catching colors and swinging beads. Short boarded hats with woven bands are common as a matriarchal status marker.

Pahk dress is more gendered than Shess garb and worker males dress as showily as the entourage if they can get away with it. Completely covering dresses with fluttering insect wings, clattering round polished shells, and swaying tassels is the fashion. Cutlines on male dress can be extremely revealing, showing off the entire lower back all the way past the hips. Female worker wear is quite drab and functional in comparison, favoring simple lower body skirts and cloaks. Matriarchs tend to wear eye-catching clothing like males but with much more conservative hemlines.

Antler drilling and dangling metal jewelry through the holes are common practices among the Pahk. Drilled antlers are not kept but jewelry is often reused every year when the antlers regrow.

Centaur cultures vary a lot on the issue of clothing coverage modesty, but tend toward more exposure than human cultures. During the scorching hot summers of the polar latitudes, most settler centaurs wear little to no clothes besides pockets, bags, and sun protection on areas of the body with no feathers. Nudity within the territory of one’s own clan is often acceptable, but coverage is expected when traveling or visiting the land of other clans. In cultures that expect modesty coverage, the genitals and belly are the areas most frequently expected to be covered.

Coverage expectations also frequently vary between different clan roles. Nudity and near nudity in workers is often seen as normal, especially for certain labor jobs. Entourage members usually have stricter coverage rules and higher expectations for personal decoration. Modesty and beautiful garments are seen as a way of demonstrating their loyalty and mate fitness to their matriarch.

Nursing matriarchs usually have their own sets of coverage rules. Since the spinnerets sit right above the rest of the reproductive bits, if the local culture takes issue with public genital exposure, they take issue with showing off spinnerets. Centaurs in coverage-mandatory cultures who are currently feeding pupa generally have the spinnerets loosely covered by a maternity sling or shirt; or have the entire operation covered with an overjacket and chausses, depending on how cold it is and local custom.

Much like everything else, the introduction of alien technology and trade goods threw a wrench into centaur dressing habits.

Glasses, monocles, and corrective lenses have been widely adopted by centaurs in order to read alien text, and these are frequently embellished with jewelry touches to make them a kind of status item.

Synthetic fabrics and cheap fabrication are taking over the Shess and Pahk regions in particular, and the cuts of garments made by centaurs on imported tailor machines often borrow from the cuts of human and avian fashion. Alternative fashions are being more frequently adopted by bachelor clans, female clans, and rebellious worker youths.

Anarchist subcultures of urban areas have their own unique garb, often using homeplanet materials but stripping them of their caste associations by borrowing from non-local centaur cultures, mixing and matching symbols of authority and submission, and eschewing functional garments in favor of strange cutouts and combinations. This is related to the dadaist art movement growing in contact-affected centaur communities.

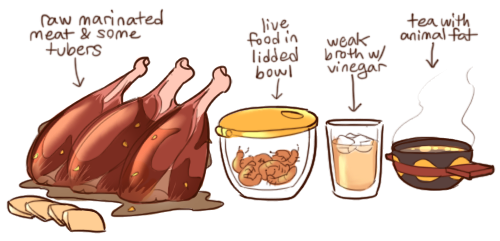

Centaurs are obligate hypercarnivores, which are fancy words that mean they need to eat a diet of 70% or more animal products to avoid malnutrition. While large game and livestock meat is obviously an important component of centaur food, their diet also includes a wide variety of invertebrates, eggs, silk and its byproducts, seafood, shellfish, bones, blood, offal, and sometimes even the contents of other animals’ guts. Heat cooking is extremely popular for its ability to transform raw materials, extract more nutrients, and preserve foods; but centaurs are also perfectly comfortable eating raw meat and sometimes even live small animals. They have strong acid and enzymes in their stomach that neutralize a lot of the bacterial growth that would prevent other sophonts from eating days old, room temperature raw meat.

While the centaur gut is short and not suited for breaking down plant matter, opportunists have found ways to process and cultivate plants into tastier forms. Starchy rhizomes, tubers, nuts, and seeds are popular crops among settler clans; often pounded into dough and steamed, fried, or roasted to supplement heartier main courses. Rougher plant matter and herbs are sometimes processed with enzymes taken from the digestive glands of herbivores and used to flavor or preserve food. As a result of their evolutionary history centaurs cannot taste simple sugars, but they can detect some starches and greatly enjoy them, along with plant-derived fats and oils. Too much of these in a diet are fattening, though.

Nutritionally plants lack several important macromolecules that centaurs cannot synthesize in their own body, so while settlers often stretch their diets with more plant matter during lean years with poor fishing, livestock, and game yields; doing this for too long results in severe malnutrition. In adults “plant starvation” causes brittle skin, muscular degeneration, feather loss, laminitis, and in severe cases, seizures and blindness. In young centaurs, plant starvation can severely stunt growth and result in reduced joint cushioning and twisted limb development, where the bones grow in a bowed curve.

Many nomadic cultures view the (relatively) large amounts of plant matter in settler diets as revolting, and consider most plants unfit to eat. Obviously there is some physical basis for this aversion, given the potential harm of plant starvation, the difficulty of digesting plant matter, and because centaurs have poor tolerance for many of their native flora’s phytotoxins—nomadic populations especially. But it is primarily a cultural aversion. Nomads view plants as animal food, and unclean until they are processed by the flesh of other animals, since plants grow from dung and rotting corpses. Some nomads have taboos about eating scavenger animals for similar reasons. Some common insults nomads call settlers translate to “dung eaters,” “livestock,” and “herbivores.”

Centaurs have a variety of tactile writing and recording methods, but oral history has been overwhelmingly important to them as a means of recording and disseminating information, especially for nomadic groups. In many settled regions, the arrival of nomads is the arrival of a new current of information from upstream. Settlers with peaceful nomad relations will usually exchange news or performance of history for passage or guest-stay.

Performance of oral history may be simple memorized speech, but it is often set into rhyme, meter, and music to assist memory. Instrumental accompaniment is common. Tellers may incorporate motions and call for audience participation with certain elements, such as claps, stomps, calls, and echoed words. Some performances may feature entire dances, multiple tellers, or a band of musicians. Bachelor clans are known for flashier (and racier) performances of histories, myths, and legends; while traditional nomad clans tend to focus more on accuracy and informational density.

In the modern day, radio and wax cylinder recording are used as an extension of this. Typically urban radio towers are owned by large clans or are a multi-clan effort, and transmissions tend to be a rotation of guests from nomad groups and local settled clans. Broadcasts are an eclectic mix of news, entertainment, and a blend of both; as is often the case with oral history. News is frequently biased to the perspective of the clan(s) controlling the tower. Recordings of oral history and performance are often common trade goods to rural clans.

For communication between individuals, two-way radio was most commonly used pre-contact. To maintain privacy on calls like this, clans would often develop coded speech.

Centaur vision is shortsighted and their visual processing biased towards motion-tracking, with more difficulty parsing dense patterns than other sophonts. Their visual art tends to include elements of motion and large blocks of color, with texture differentiation being an important element of items that are meant to viewed closer and handled. Mural art is popular for decorating buildings and visual scripts are most often used for signage. Representational art styles are more commonly seen in sculpture while paintings and drawings lean more into abstraction.

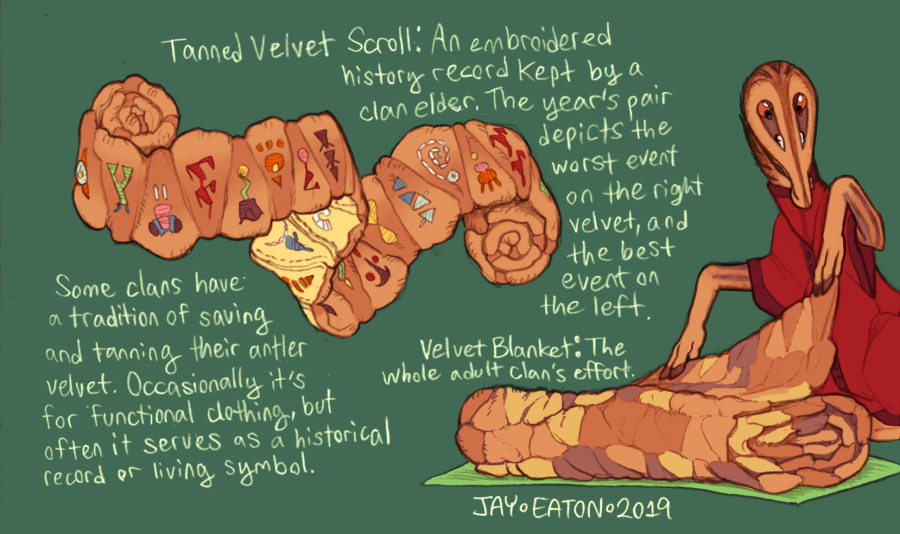

Using animal materials in artwork is very common, including beautiful feathers, tanned hides, invertebrate wings and exuviae, bones, and more. Even animal parts originating from other centaurs are seen, in particular shed antlers, which are a popular source for tool handles and art carvings. Some centaurs will even save the velvet that grows over their antlers and peel it off carefully in one piece once it is loose over the bone.

Sunchasers cut them off into a rectangular piece that can be tanned into leather and then be sewn together with other rectangles. Some clans use this velvet leather to make sacred garments, some keep large blankets. These grow every year, as new shed pieces are added from clan members. Sometimes all clan members contribute, sometimes only the current matriarch. The individual triangles may be embroidered with large colorful thread to represent the important events of the year.

The Shess generally do not save their velvet but will often keep their shed antlers, which are customarily decorated with scrimshaw, carvings, and dye. The central dwelling of a Shess clan compound usually has a wall decorated with old antlers. The technique varies. Sometimes the bones are stacked and cemented into the wall, sometimes they are drilled and woven into a thick hanging curtain, and sometimes they are set into the wall or ceiling so that they bristle outwards.

Most pre-contact centaur technology was artisan goods. In urban areas, a single clan would often specialize in a specific area of technology or design and hand-make items to order for customers in other clans. This system is somewhat similar to “family careers” found in bug ferrets, where the family functions as an individual in a profession who can be hired or hire. However, centaurs are more likely to have individuals within their families who do not participate in the clan’s dominant profession and may work elsewhere, or have hired individuals from other clans.

While urban centers often had larger manufacturing operations and higher degree of specialization that allowed more complex technology to be made, mass production and factory operations that required a large workforce of unrelated centaurs were mostly unheard of.

Sports are common source of entertainment within clans and a method of strengthening interclan relationships, or competing with other clans in a less destructive way than war.

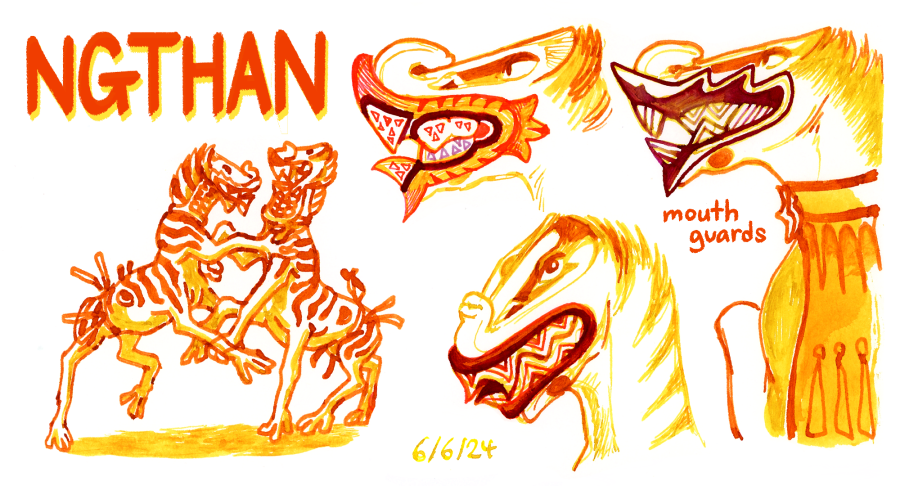

Wrestling, matched combat, duels, and contests of strength are common between young related females competing for matriarch consideration. These fights have strict local rules that must be adhered to for a victory to be considered honorable, and though some duels are to the death, it’s not terribly common for deadly force to be approved. Hand-to-hand dueling rules often forbid the mouth to be opened during the fight, since bite wounds can often be fatal or disabling. To make this easier for the combatants, they may be given a mouthpiece to hold with their teeth.

In the Shess region, a very popular kind of hand-to-hand duel is ngthan, which is often held for inter-clan tournaments as well as intra-clan duels. Ngthan combatants have elaborately carved mouth guards that cover a large portion of the face and jaw and usually feature brightly painted, exaggerated teeth and snarls. The fighters are otherwise nude except for a band around their rear waist that has flags tucked into it. The goal of the battle is to grab all of the flags off of your opponent. Ngthan fights are generally held in late spring in dedicated amphitheaters, as they attract large crowds. Radio coverage of these events (and post-contact, streaming) is extremely popular.

Hunting parties and hunting sports are a popular rural past time. Allied clans will strengthen bonds and socialize by forming hunting bands, who will travel together on the territory of the host and hunt large game and camp and cook together. Hunting sports are more commonly held within a clan by workers for their own entertainment, and usually involve a live captured animal that one or more centaurs will release in a closed space and then attempt to catch without weapons. Typically the animal is eaten afterwards. A more common version of this in urban areas uses a livestock animal as the victim instead.

Alien technology is rapidly supplanting traditional radio formats and oral history on the homeplanet, and the art scene in areas mostly heavily effected by first contact has taken a dada-istic turn. New abstract art forms have emerged, embodying a zeitgeist of helpless nonsensical change, disruption of tradition, and mixing local and alien power structures. Nothing makes sense anymore, why should art?

The BFGC established first contact with centaurs in 2251, shortly after throwing a wormhole into their stellar system and confirming the presence of sapient life. This decision was not popular with avian or human governments.

The BFGC’s perspective is that contact with sapient life should be established as quickly and safely possible so that technology can be shared and standards of living can be raised for the party with less complex technology. Humans and avians tend to view this as either an unnecessary risk that could result in war, or as a form of “soft colonization” in the case of low-tech sophont cultures. The former standpoint sees the BGFC’s intervention as, functionally, handing a gun to a stranger and trusting them not turn it on you. The latter standpoint sees the abrupt addition of alien technology to centaur cultures as a move that denies them agency by supplanting their native technology; erasing a potential future with unique technological insights that could be developed by centaurs independent of foreign meddling.

The largest embassy sites are currently in the urbanized coastal regions of the Shess and Pahk regions. The largest alien presence there is the technology outreach branch of the BGFC, which works to distribute technology and establish the infrastructure necessary for it to work. Biomedical research and communications technology are their two primary concerns. A handful of human governments also have embassy sites on the centaur homeplanet, mostly, it seems, as a measure to insert their agenda where they can and monitor what the BFGC is up to. Avians are mostly absent, as the Dominion of Tiiliit views the centaur homeplanet as a liability and a waste of money. Some other avian governments from the Iiyaie Federation and Hotsuuv Nations have embassies, though.

Centaur attitudes towards first contact vary wildly, and many rural centaurs outside the nomadic paths are still unaware it’s even happened. Within urban centers most affected by contact, it is broadly popular with powerful clans as the BFGC’s technology and their proximity to the majority of new infrastructure has only increased their power and influence. Rural clans and smaller urban clans are often bitter about growing power imbalances. Many resent aliens, but are fearful of attacking them, resulting in more interclan conflict than interspecies conflict. While wars between clans were not infrequent pre-contact, alien meddling has changed how they are conducted. The BFGC’s taboo for physical violence has led to them manipulating clan conflicts and withdrawing support in ways designed to end overt war as quickly as possible; but their blind eye to less overt tactics has created an epidemic of espionage, covert terrorism, and economic exploitation.

Accommodation for centaurs in space is still extremely limited due to their large size, highly carnivorous diet, and low medical understanding of their physiology.

Centaurs travelling off the homeplanet mostly eat from food printers, which use a combination of native centaur microbe cultures and synthesized macromolecules to create rough approximations of sausage or tuber pastes. The flavor and texture of these is uninspiring, but they do allow centaurs to indefinitely visit alien colonies that have these food printers without fear of starvation or having to rely on expensive exports of homeplanet foods. Establishing centaur agriculture in space is more difficult than for other sophonts because of their highly carnivorous diet. Animal agriculture usually requires a backbone of plant agriculture and horticulture first, the products of which can’t be sustainably eaten by centaurs. Spacer efforts to feed visiting centaurs has only recently moved onto live animals, with invertebrate farming supported by microbe culture diets.

Centaurs off their homeworld are considered an oddity by most other sophonts, and tend to be regarded with curiosity, suspicion, fear, or annoyance. Many sophonts’ preconception of centaurs doesn’t extend past “large scary carnivores who don’t understand technology.”

Most centaurs in space are visiting, but the few who decide to stay are usually nomads. This is for a handful of different reasons: nomadic ethnicities are smaller, and tend to fit better in conventional craft. They don’t have territories, and are used to roaming, so roaming into space involves giving up less. Many also consider going into space a kind of spiritual journey to visit the mother of creation, and see the numerous other children on her back, the stars. Spacer centaurs tend to flit between odd jobs wherever they can find them, often bringing their own printer food supply with them. The colloquial term for them in English (loosely translated from nomadic centaur dialects) is starchasers.